The Historic Home That Taught Me to Listen

❦

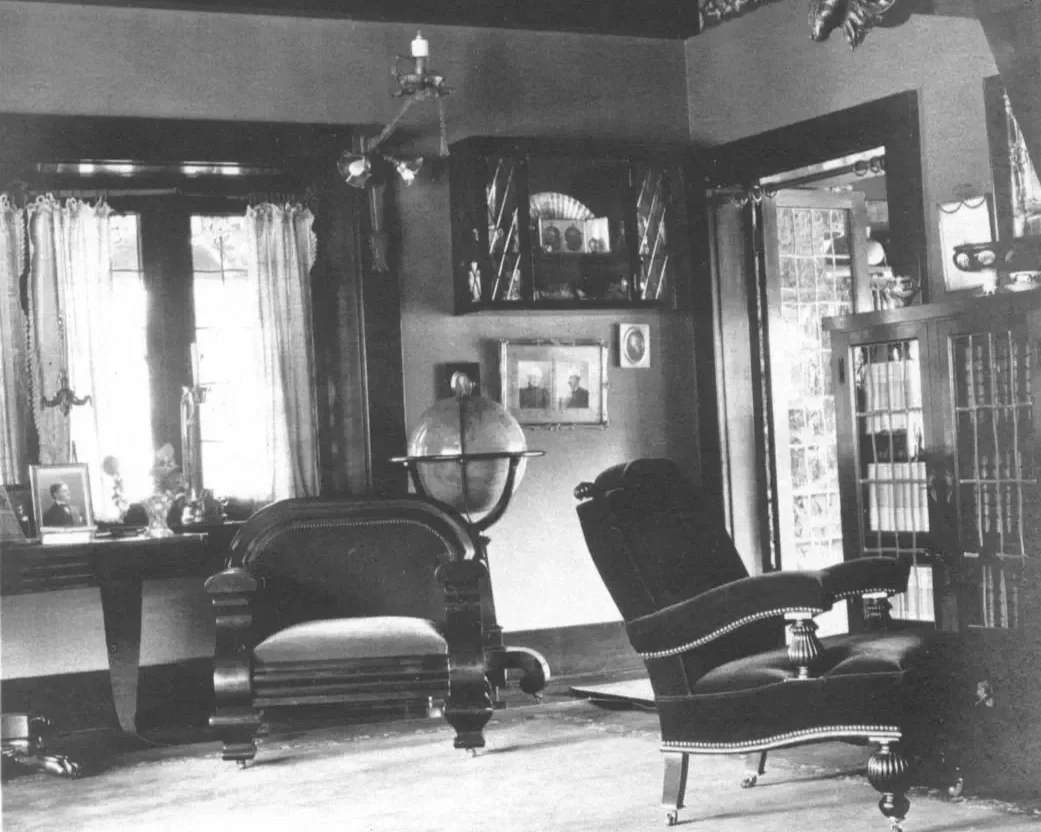

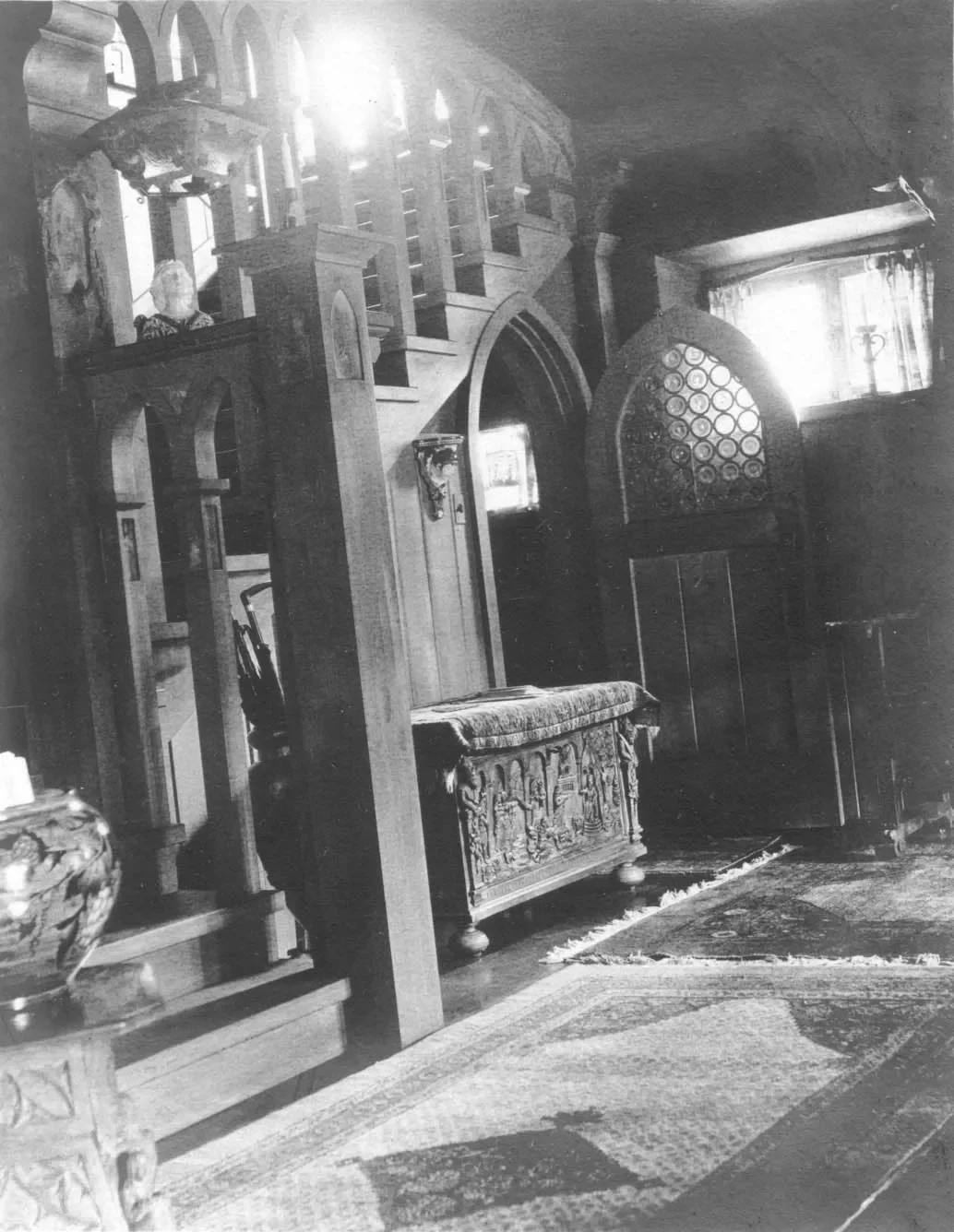

I spent a lot of afternoons wandering the halls of Greystone, Olive Arms' mansion-turned-museum on Wick Avenue. At sixteen, I was the youngest docent the Arms Family Museum had ever hired. I loved giving tours to visitors who came in expecting a stuffy museum full of antique firearms and instead found themselves seduced by Olive's Arts and Crafts sensibilities. Between tours, I had the immense privilege of simply existing in the historic space. While other teenagers were folding sweaters at the mall, I was absorbing an environment where every wallpaper pattern, every chair, every slightly-too-precious knickknack was saying something—if you knew how to listen.

The house trained me to tune in with something beyond my ears. I learned to notice how morning light slanted differently than evening light through lace curtains. How the stone floors seemed to remember the footsteps they'd carried. How the tranquility Olive imagined for her home in 1905 somehow still hung in the air, decades after her death.

I didn't know it at the time, but this was my first real apprenticeship in the skill I use most today.

Olive's Philosophy

Olive Arms had passed years before I arrived at Greystone, but her presence was everywhere. She'd built the house as her ideal home and had also written down why. Her essay, "The Story of My House," presented to the Friday Literary Club of Youngstown, became my accidental manifesto.

“Make your home personal by having in it, things you really take an interest in: this makes the atmosphere of your house express you.”

She understood something it would take me years to fully name: authenticity has nothing to do with following rules. It's about honoring what calls to you—especially if no one else gets it.

"If we have ornaments or furniture for which we have sentiment, even if we should not consider them good, but if we like them, and it would not be home without them, then we should use them, and try to build around them a background becoming to them.”

This wasn't just decorating advice. It was a guide for living in the world on your own terms.

The Art of Seeing

❦

The library was my favorite room, the one that quietly got under my skin. Olive had written about books as vehicles for travel—"You have but to step on board one of the numerous crafts in waiting… and set sail for any part of the universe."

But the room itself told its own story: the arrangement of the shelves, the chair angled just so for reading, the writing desk that did in fact invite you to sit down and write. She knew that objects, like people, give off signals about how they want to be approached.

Once I started noticing those details—the height of a portrait, the way a window framed a specific view, the careful staging of a prized vase—it was like slipping on a pair of glasses I couldn't take off.

What the House Taught Me

Wandering Greystone's halls taught me how to notice what other people miss. How to make the past accessible without sanding off all its mystery. How to let artifacts and documents speak for themselves without shoving them into someone else's script.

Those same instincts shape my work today at the Office of Special Collections. Whether I'm sifting through military records at the National Archives or piecing together battlefield communications at the Imperial War Museum, I'm still using the patience Greystone demanded—the patience to wait, to listen, to let the thing tell me what it is.

Looking back now, I can see how profoundly this first job shaped my professional trajectory. When the Library of Congress interviewed me about my work there, I found myself leading with the Arms Museum experience - describing how it 'instilled in me a deep love of history, architecture, and design.' What felt like just a teenage job at the time had actually become the foundation for everything that followed.

Olive knew that houses, like archives, aren't just storage. They're living environments where meaning accumulates through the choices people make—what to keep, how to arrange it, and why it matters. Every document I touch, every photograph, every oral history is someone's attempt to create what she called "backgrounds becoming"—a setting worthy of the story it holds.

Coming Home

The other day, while working on the Gommecourt project, I realized I was doing exactly what sixteen-year-old me used to: waiting for visitors, preparing to make the past feel alive, holding space for voices that might otherwise vanish.

Greystone taught me that the real work happens between the official narrative and the lived experience—where the authentic voice still whispers to anyone patient enough to hear it.

The Office of Special Collections isn't just my business. It's my way of making a home for those voices, the kind of home Olive Arms would have recognized instantly.

❦

The Arms Family Museum is part of the Mahoning Valley Historical Society in Youngstown, Ohio, still preserving Olive's vision at 648 Wick Avenue.